Suzy Parker: American model and actress born 28 October 1932, Long Island City New York; died 3 May 2003, Montecito California. On screen 1957 – 1970.

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

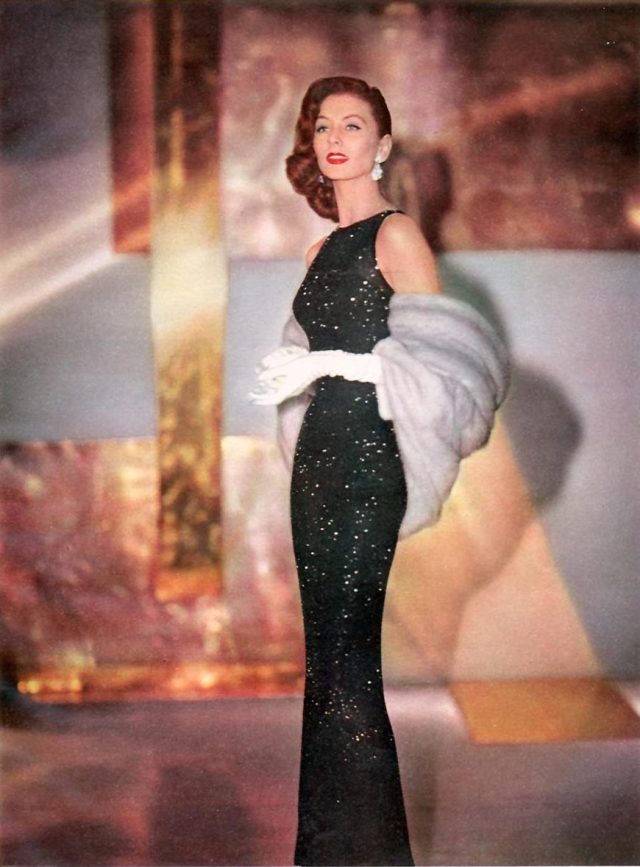

After World War II in the world of Couture Fashion the Super Model was born and her name was Suzy Parker. There were plenty of other women who might claim that title but to me especially in the late 1940s and all through the 1950s Suzy Parker had more magazine covers then any other model even her sister Dorian Leigh. Unlike any fashion model before her, Suzy Parker was on a first-name basis with the world, bringing her own radiant personality to every shoot. Hitting Paris in 1950, at age 17, under the wing of her already famous older sister, Dorian Leigh, she went on to wow Christian Dior, became a muse to Coco Chanel and Richard Avedon, and fell for the dashing count she would secretly marry. But even when Hollywood beckoned, Parker never really cared for the glitter and the glamour of the modeling world, she found her greatest happiness at home. Suzy Parker was born Cecilia Ann Renee Parker in Long Island City, New York, to George and Elizabeth Parker on October 28, 1932. She had three older sisters: Dorian, Florian, and Georgiabell. Suzy’s original name came from three of her mother’s best friends. Parker’s father George disliked the name Cecilia and called her Susie, a name which Parker would retain throughout her life. A French Vogue photographer later changed the spelling to “Suzy”. Suzy Parker’s photo appeared in Life magazine when she was 15. Parker became Avedon’s muse, she said years later that “The only joy I ever got out of modeling was working with Dick Avedon.” She became the so-called signature face of the Coco Chanel brand. Chanel herself became a close confidante, giving Parker advice on men and money as well as creating numerous Chanel outfits for her. When Suzy Parker signed with the Eileen Ford Modeling Agency, how important was the fledgling model to Ford’s fledgling business? “How would you like to guess the answer to that?” asks Eileen with a laugh. “Wildly. There aren’t many Suzys in the world. God didn’t create them.”

“Don’t forget,” says actress Ali MacGraw, who styled a shoot with Suzy in the 60s, “this was the day before anyone got retouched. You could not go out and make a Suzy Parker.” She was the first model to earn $200 per hour and $100,000 per year. Vogue declared her one of the faces of the confident, post-war American woman. It would be easy to name Suzy as the first supermodel. For much of her career she was the highest-paid model in the world, her rate always double that of her peers. In fact, the word is too small for her. Suzy loved the freedom she derived from her earnings, but her spirit was searching. As much a personality as a beauty, she was the first model America cared about, and hurt for. On December 21, 1956: Edward R. Murrow’s Person to Person gives America a captivating Christmas present. She is five feet ten, a slim figure of a woman in a dark Chanel suit, her hair a tumble of copper that even on black-and-white television has a new-penny glint to it. With the poise of a princess, she shows the country her Sutton Place penthouse. As the interview progresses Murrow asks, “is it too cold to see the terrace?,” so the camera follows this heavenly, singular girl out the French doors into a New York night of ghostly glows. “It’s getting a little bit foggy now,” she explains, “but it’s sort of lovely. It’s like being on a boat.” And so she sails through her living room and across the country, the first American model on a first-name basis with the world: Suzy. It had all happened and was still happening for Suzy Parker in 1956. She was 24 and at the peak of a modeling career that was arguably the biggest in the history of the business. Christian Dior, the reigning king of 50s fashion, called Suzy “the most beautiful woman in the world.” Coco Chanel, fashion’s dowager queen, mentored the young American, mothered her, and in 1954 looked on Suzy as the muse of a newly global Chanel. Joan Crawford herself weighed in. “I think that face,” she said, “is the most fabulously beautiful thing I have ever seen in my whole life.” And the smile. Suzy had half-smiles, mystery smiles, sly, knowing, and slow smiles, but that million-dollar Suzy Parker smile, pure phenomenon framed by deep-dish, apple-pie dimples, it was a thing unleashed — sunshine and thunder. All her life she would joke about the luck of her high cheekbones, but Suzy’s smile — there would never be another one like it. Hollywood had noticed. Her first film role was in Kiss Them for Me (1957), playing the main interest of Cary Grant’s character. Soon after she accepted a cameo role in Funny Face (1957), on screen for two minutes in a musical number described as “Think Pink Number”. Her other films include: Ten North Frederick (1958), The Best of Everything (1959), A Circle of Deception (1960) during which she met future husband Bradford Dillman, Flight from Ashiya (1964), Chamber of Horrors (1966) and dramatic roles in TV shows such as Burke’s Law and The Twilight Zone plus appearances as herself on a number of quiz shows such as I’ve Got a Secret. In 1958, Parker was a passenger in a car her father was driving when they were hit by an oncoming train. Supposedly neither her or her father heard or saw the train until it slammed into the car. Her father died of his injuries at the hospital. Parker was hospitalized, with broken bones and embedded glass (with her face untouched).

It was after marrying her third husband, actor Bradford Dillman, in 1963, and suffering injuries in another minor car accident in 1964, she mostly retired from modeling and acting. In the mid-1990s, Suzy developed an ulcer because of all the cortisone she’d taken for her allergies. “I don’t have ulcers,” she told the doctor. “I give ulcers.” It required surgery, and Suzy almost died on the operating table, but was resuscitated with a massive dose of prednisone, and was never entirely healthy afterward. There were hip surgeries, more ulcers, the onset of diabetes. The last five years of Suzy’s life were spent in and out of the hospital, hopeful, then discouraged, then hopeful again. In the winter of 2003, when her kidneys failed and she had to go on dialysis, the loss of freedom was crushing. “I just keep thinking,” she said to her friend Nancy Failing, “If I can make it through until this orchid finishes blooming I’m going to be O.K.” But the nature of her resolve changed. She said to Vit, “I have put Bradford through enough.” And to Kitty D’Alessio, “I want to go.” And finally, to Dillman, “I’ve made the decision. I’m no longer going to have dialysis.” It was time to go home. “She saw the house,” her husband says, “and she just beamed.” Two weeks later, on May 3, 2003, Suzy Parker died with Dillman and Pamela at her bedside. She was 70.